Lycoming County native became Philly’s 1st woman detective

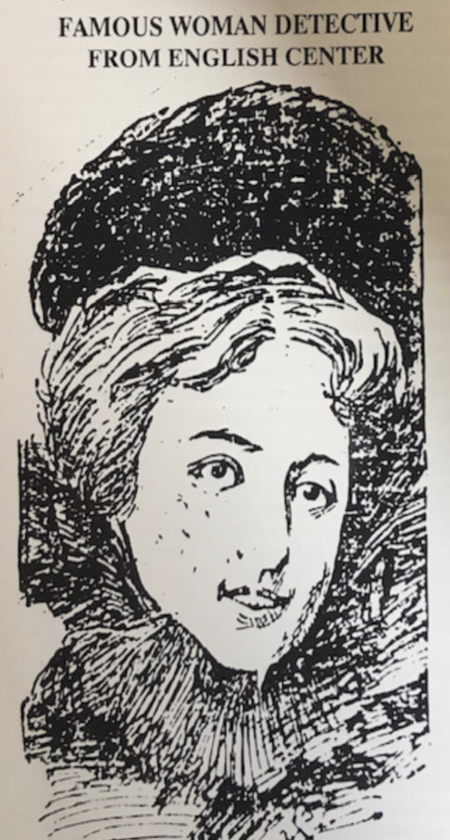

IMAGES PROVIDED A sketch of Laura E. Ratcliff from an 1899 edition of the Williamsport Sun and Banner.

One afternoon while I was volunteering in the Genealogical Society Library, I picked up a book titled History of Little Pine Valley by Harry Stephenson, Sr. (1992). As I began looking through the pages, I noticed an illustration of a young lady with the caption “Famous Woman Detective From English Center.” What??

Laura E. English was born in 1866 in Pine Township, Lycoming County, to Henry and Nora English. She attended school in English Center. In the February 27, 1890, issue of Williamsport’s Daily Gazette & Bulletin, a brief article stated that Mr. Matt Radcliff, a traveling salesman for the Williamsport Candy Manufactory, had eloped the previous week with Miss Laura E. English of English Center. The title of the article was “Our Slippery ‘Bill Nye’,” a reference to a noted humorist of the time. Fourteen months later, Laura was left a widow, as Matthew died on April 21, 1891.

A woman’s place is …

If you were a woman living in the 1890s, your opportunities were limited. Marriage and motherhood were the most important jobs for women, according to societal standards. But unlike just a few decades earlier, a woman’s standing in her community was not solely hinged on her starting a family. If a family had the means to be able to hire someone to care for the home, it was considered a show of wealth for a wife to have no responsibilities at all. Many women wanted this role to change. For some, remaining unmarried was the first step toward independence. But single or not, women found that their options were largely dictated by their social class.

While an educated woman might be employed as a nurse, teacher or secretary, lower-class women had fewer options and typically were obliged to take jobs as laborers. Positions such as textile factory worker, maid and laundress were among the most common in Lycoming County. Regardless of class, women of this day were typically able to find employment only at positions considered “suitable for the fairer sex.”

Woman detective

March of 1899 found Laura E. Ratcliff — as she called herself — living in Philadelphia, where she had applied for a license as a private detective. The Muncy Luminary and Lycoming County Advertiser printed a brief article in which Laura is described as shrewd and quick witted. She had done “some effective work” and thought she could do more if she obtained a license.

In April of 1899, the Evening News, published in Williamsport, ran an article titled “Woman Detective,” which described the difficulties Laura overcame to obtain her license. Judge Abraham M. Beitler of Philadelphia refused to sign or grant the license without the endorsement of the director of public safety, Frank M. Riter. The Philadelphia Times edition of March 5, 1899, reported that Director Riter was not in favor of granting a woman a detective license and that he wrote to the judge to that effect.

In addition to being shrewd and quick witted, Laura also had experience working for a detective agency, and thus I cannot imagine that Judge Beitler and Director Riter really thought that the story would end with their refusal to grant the license. And it did not.

The power of the press … and friends

Riter’s decision to oppose the issuance of the license must have been a huge disappointment to Laura, but she did not give up. After all, she had already been doing the job; she just needed a piece of paper authorizing her to make arrests.

She had a large number of friends in Williamsport and Lycoming County, and they came forward to speak on her behalf. She was associated with the Columbian Detective Agency of Philadelphia and had traveled all over the United States doing work for them. Since she had already been on their payroll, it would not be surprising if people from that agency spoke on her behalf. They obviously knew she had the intelligence and ability to be a detective. The Philadelphia Times writer ended his article by saying that in his opinion there could be no serious objection by right-minded people to female detectives in fact as in fiction.

The building at 1001 Chestnut Street, in the “Market East Neighborhood” of Philadelphia, was built in 1873 for the New York Mutual Life Insurance Company. It originally had three stories and a mansard roof; three more stories were added between 1890 and 1891. In 1899, 1001 Chestnut Street, Room 706, was the location of the offices of Mrs. Laura E. Ratcliff, DETECTIVE!

A license granted

By April 7, 1899, Laura had been granted a license as a detective in Philadelphia, which gave her the authority to make arrests just as any city detective might. I wonder if she read any

of the articles written about her at the time. If so, was she offended by the statement that she could now capture a criminal and say “Hands up, you are my prisoner” just like a man? Or was she nodding her head and saying to herself, “Yes, I can! Just like a man . . . or maybe better”? Who would suspect that a beautiful young woman would be capable of taking down the unfaithful spouse, the absconder of funds, the confidence man?

After Laura became a licensed detective, she was appointed superintendent of the Columbian Detective Agency. I wonder what Riter thought upon hearing that.

By June of 1899, Mrs. Laura E. Ratcliff, the only woman detective in Philadelphia, was already scheduled to leave for Europe to try to locate two sons and other heirs of a Germantown man who had recently died and left an estate of $2,000,000.

Later years

By 1915, Laura had remarried and relocated to Portland, Oregon. Her husband, Charles J. Lytton, was a salesman for the National Surety Company. They were listed at an address of 1053 E. Alder Street in Portland. By 1920, they had relocated once again, to Southwest Lake Avenue in Los Angeles.

Charles died on December 10, 1928, leaving Laura a widow once again. His birthplace is given as Pheta, Pennsylvania, on his death certificate, but as I could not find a Pheta, Pennsylvania, I believe he was born in Philadelphia and that is where he and Laura met.

In the 1930 Census, a 54-year-old Laura was living at 362 Third Street and was working as a saleswoman in a retail mercantile. I could find no reference that she continued her detective work.

Laura English Ratcliff Lytton died on March 26, 1939, at the age of 72. While researching for this article, I found no record of any children born from either of Laura’s marriages. However, with the aid of the helpful volunteers at the Lycoming County Genealogical Society, a family tree was located that indicated that Laura and Matthew had a son. In yet another variation of the family name, he was called Matthew Radcliffe English. He married Sarah Weil and had two daughters and a son. I wonder if they knew that their grandmother was the first female detective in Philadelphia.

JoAnn Tobias is a volunteer at the Lycoming County Genealogical Society library. She loves history and discovering more about Lycoming County and the people who helped make it what it is today.