Muncy Creek Township resident shares fears of contamination

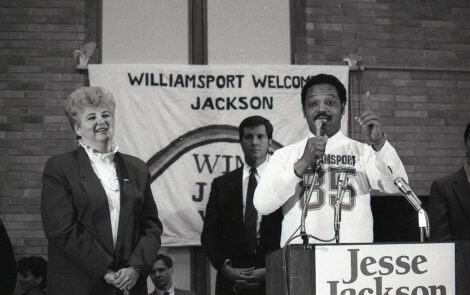

Howard Williams of Muncy gives testimony during the conditional use hearing by the Muncy Creek Township Supervisors in Muncy. DAVE KENNEDY/Sun-Gazette

A Muncy Creek Township resident who testified previously to the U.S. Senate and House on chemical and toxic contamination issues, views the Sunny Side Up Farms’ concept as one that would, as presented, adversely affect the health and safety of neighbors and adjoining property owners.

The proposed concentrated animal feeding operation (CAFO) of 350,000 free-range chickens in the five barns may produce a pungent odor, which, under certain weather conditions, would not only be detectable as low ranges of particulates in the air, but could, at higher ranges, actually be tasted, according to a study presented during testimony Wednesday before the Muncy Creek Township supervisors by Howard Williams, a former vice president of Construction Specialties.

What he presented, he said, was not a risk analysis, but rather a detailed report, the vast majority of which was evidence-based. The presentation also was in a binder given to appropriate parties like the supervisors and developer and their attorney, Samuel E. Wiser Jr. along with Zachary DuGan, attorney for the Muncy Area Neighborhood Preservation Coalition.

Williams was not there to represent viewpoints of the coalition, a citizens advocacy group that is opposed to the agrivoltaic project of the chicken farm and solar array on the site.

With vast knowledge of chemicals, Williams gave a background that included him being invited to testify before the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Superfund and Toxics and Environmental Health in support of the now-updated Frank Lautenberg Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), enacted about 10 years ago.

Moreover, Williams said he was invited to testify at the U.S. House of Representatives in that regard, and gave reports and testimony to the United Nations Committee on Chemicals and Products, and has given such reports across the nation and world – in Boston, Geneva, Belgrade, and Nairobi.

Williams’ presented numerous data points, including one section of the report where he noted data on particulate matter in the air that could be picked up by the human olfactory sense (smell), which even at low levels becomes detectable, and if there is a high enough concentration, the particulates in the air could actually be – tasted.

It, admittedly, went against some of the points in prior testimony made by Cody Snyder, of Ag Ventures, a company that would be a daily operator of the proposed CAFO, who remarked how the farm would be strictly operated in accordance with all environmental state and federal regulations and would be required to have a nutrient management plan in place.

The manure, for example, would be enclosed, not spread locally, and removed on occasion by truck to be transported off-site. However, when that process occurred there might be uncontrolled odor, according to the prior testimony.

The material Williams used included the rather generic terms in scientific fields such as “receptors,” but he said, “Or, I prefer to say people, my neighbors.”

Asked about that, Williams said code calls people receptors, sterilizing it, essentially making people out to be inanimate blobs, but they are people.

While his power point presentation was not available on the screen for the audience, on one page (Page 8) of the report, Williams listed a section on motor sensory exposure and quality of life effects.

The particulate rates on it were colored and maximum concentrations were shown indicating the rings or a ring or circular distance from the center of the site outward. Rates match or closely match distances that might be involved in this CAFO, he added.

Basically, going down to the bottom it revealed a unit measure of 1 informs the viewer that, scientifically, the average person is going to smell it. A unit measure is a standard by which chemicals are evaluated and quantified on the odor level. As it goes up, there are various health effects relative to the rise of that, he noted.

At 100 odor units, “you can taste it,” Williams said, adding the reason is because the particulate is on the olfactory, or inside nose. Levels of particulars were seen as high concentrations of particulates within the 500 foot zone, the 1,000 foot zone, or beyond 10,000 feet. The rings on the map go from 500 feet to 10,000 feet with corresponding numeric value of the odor, he said.

These are what is a screening level analysis and they are predictive and certainly not guaranteed, he added.

Meanwhile, Williams’ attorney, Robert Davidson, of Bloomsburg, clarified his points for the board.

“Based upon the diagram with a concentric ring, that shows the area that they performed the work that they do … that would be potentially impacted by odors that might be emanating from this property,” Davidson asked. “That is correct,” Williams affirmed.

Bring in a pro

“I am saying that under any circumstance that an AERMOD should be done,” Williams said.

An AERMOD is a “more sophisticated test,” he explained.

The (test) or (screen 3 analysis) that Williams used is considered preliminary and used to determine whether or not there is enough indication to go to the next level. He implored supervisors to have that kind of more intensive test done.

“Because you (supervisors) are going to make a decision on human health,” he said. “This is simply a screening or indicator that the magnitude of the emissions warrants going to a pro and having that done.”

Davidson added, “You have concerns based upon concerns on the work that you’ve done related to the odors which also contain particulate matter … that may pertain to a nuisance factor … but also specifically a health factor.”

“This is not a risk analysis, not a certain outcome, but related to the total chemicals that are in the emissions,” he said.

The kind of chemicals in the air that can be produced by the operation of such farms include chemicals of “very high concern, chemicals of concern and chemicals of very high volume,” Williams said.

These are chemicals that are on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s priority pollutant list, he added. “They are on the list because they are not good for us.”

Water usage disputed

Among the arguments presented was the amount and impact on groundwater supply for the operation of the CAFO.

Snyder previously cited a figure of 17,500 gallons per day, but Williams testified that the narrative does not provide sufficient evidence to support that amount of poultry in the barns.

He cited an example of how it was possible that “heat stress on the birds” could impact the amount of water needed, and other factors.

“If hens are not given enough water the quality of the eggs suffer,” he said.

He further said there would be water needed as part of the bio-security measures taken by operators of the farm.

Williams alluded to the testimony of two hydrogeologists on the potential for a high capacity well on the site to draw water away from neighboring wells.

Wiser, throughout, frequently objected to Williams claims and said they were “inadmissible” because he was not an agriculture specialist, nor was he an expert in hydrogeology or meteorology, and was using assumptions “without first-hand knowledge in these scientific fields and was using third-party information that was “inadmissible and irrelevant.”

Davidson disagreed, citing that information presented by Williams included what was in published documents.

Wiser also will have further opportunity to cross-examine Williams and the evidence presented.

That is how it should work, Williams said in a follow up.

“My testimony is evidence based and not opinions,” he said. “The process is working the way it is supposed to.”